Remembering Russell Malone: A Jazz Guitarist’s Legacy

The unexpected death of Russell Malone on August 23, 2024, left the jazz world in shock. Malone collapsed from a heart attack while on tour in Japan with bassist Ron Carter’s trio, passing away at age 60. As a lifelong admirer of his music, I felt compelled to write this memoriam to honor an exceptional guitarist who bridged generations of jazz. In the days after his passing, tributes poured in from fellow musicians and fans, all testifying to Malone’s warmth, humor, and mastery of the guitar. What follows is a chronological tribute to his life and career a celebration of both the man and his music.

Early Life and Musical Roots (1963–1987)

Russell Malone was born November 8, 1963, in Albany, Georgia. Some of his earliest memories were of Sundays in church, captivated by the gospel choir and the guitarist accompanying them. His mother nurtured his fascination by buying him a toy guitar when he was just four years old. By age six he had graduated to a real guitar and was skilled enough to play along with the church choir. Growing up in south Georgia, Malone absorbed a rich mix of musical influences – gospel from church, down-home blues, and country tunes on the radio by the likes of B.B. King, Glen Campbell, and Chet Atkins.

A pivotal moment came at age twelve: Malone saw jazz guitarist George Benson performing on television with Benny Goodman’s band, and it changed his life. “I had never heard anybody play the guitar like that before,” he recalled, noting the joy and passion on Benson’s face as he played. From that moment, young Russell fell in love with jazz guitar. Largely self-taught, he voraciously learned from recordings and emulated his heroes. Years later he would humbly credit those pioneers, saying: “I’m standing here in the shade today because of people like George Benson, Wes Montgomery, Pat Martino, Barney Kessel… those men planted that tree a long time ago.” This deep reverence for the jazz guitar tradition would remain a hallmark of Malone’s character and playing.

After graduating from Monroe High School in 1983, Malone moved to the Atlanta area to pursue music. He gigged around Atlanta’s jazz clubs and honed his craft throughout the mid-1980s. A breakthrough came in 1987 when legendary jazz organist Jimmy Smith heard the young guitarist play. Impressed, Smith invited Malone to sit in during a show. By the next year, 1988, Malone officially joined Jimmy Smith’s touring band. This was the start of Malone’s professional career – an informal “apprenticeship” that immersed him in the bluesy, soulful world of organ-combo jazz. Night after night on the road with Smith, Malone refined his groove and learned to deliver searing solos and tasty rhythm parts. Fellow guitarist Henry Johnson recalled first hearing Malone on tour with Jimmy Smith: when the band dropped out and Malone played a solo passage “doing all those harmonic things that he does so well,” Johnson was blown away. It was clear that a major new guitar talent had arrived.

The First Meet Russell Malone with Jimmy Smith

Breaking into Jazz: With Harry Connick Jr. and Jazz Stardom (1988–1994)

After two years with Jimmy Smith’s group, Malone’s reputation as a versatile sideman was growing. In 1990, he landed a high-profile gig with singer/pianist Harry Connick Jr., who was then at the peak of his popular success. Malone joined Connick’s big band, bringing his swinging guitar to the ensemble’s energetic mix of New Orleans jazz and big-band pop. For four years, Malone toured the world with Connick Jr. and appeared on several of his recordings. This period gave Malone exposure beyond the jazz clubs performing on TV shows and large concert stages, he reached audiences who might not have known him otherwise. It also led to his first major recording as a leader.

In 1992, while still with Connick’s band, Russell Malone recorded his self-titled debut album Russell Malone on Columbia Records. Connick even contributed on piano for the album. Malone’s debut announced him as a bandleader in his own right, featuring his elegant arrangements of standards and showcasing his clean, soulful guitar tone. He followed it with Black Butterfly (1993) on Columbia, further establishing his solo voice. Critics praised Malone’s blend of classic jazz guitar influences with Southern blues feeling – a style that was rooted in tradition yet unmistakably his own.

By the early 1990s, Malone was being noticed as part of a promising young generation in jazz. He became friends with peers like trumpeter Roy Hargrove, bassist Christian McBride, and pianist Benny Green, all rising stars who would frequently collaborate with Malone. In 1995, one of Malone’s biggest career turns arrived: he was recruited to join Diana Krall’s trio.

Mainstream Spotlight with Diana Krall (1995–2000)

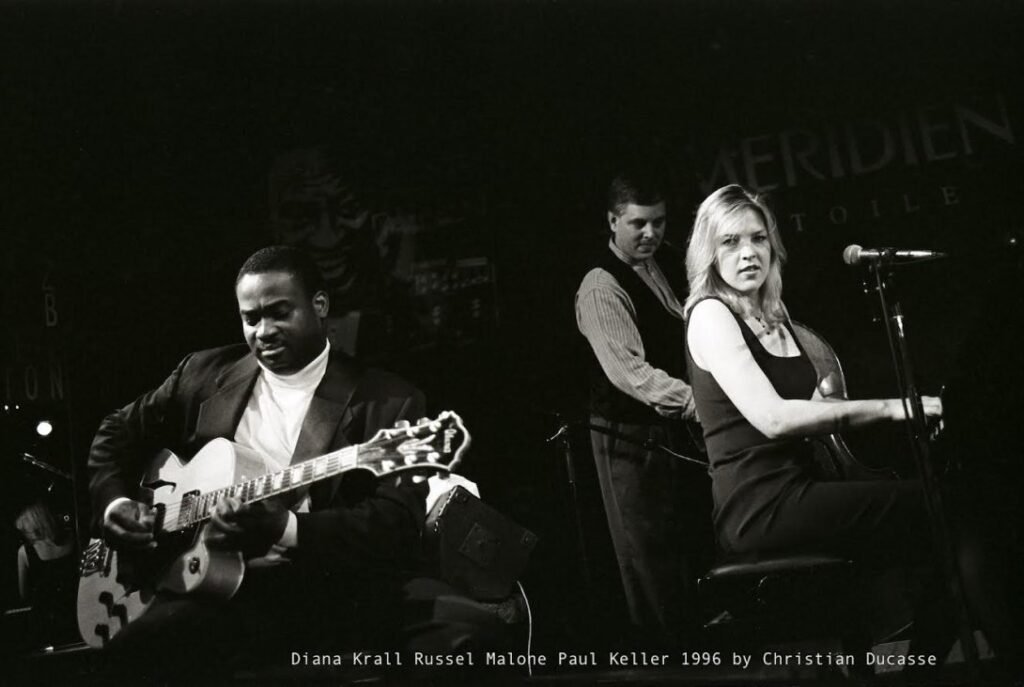

In 1995, pianist and vocalist Diana Krall, who was rapidly gaining fame, chose Russell Malone as her guitarist. Malone became an integral member of the Diana Krall Trio, playing on her albums and tours during a period when Krall’s career skyrocketed. With his suave comping and melodic solos, Malone added a warm, swinging underpinning to Krall’s intimate vocal style. He appeared on three of her albums that earned Grammy nominations, including All for You (1996) and Love Scenes (1997). Notably, he played on When I Look in Your Eyes (1999), which won the Grammy Award for Best Jazz Vocal Album. The live album Diana Krall Live in Paris (recorded in 2001, released 2002) also featured Malone and went platinum, bringing his playing to an even wider international audience.

Night after night on stages around the world, Malone traded solos with Krall’s bassist and locked in with her piano, delivering tasteful fills and bluesy riffs on tunes like “Peel Me a Grape” and Nat King Cole Trio standards. Fans can witness his rapport with Krall in concert footage for example, a 1996 Montreal Jazz Festival performance of “Route 66” where Malone’s solo swings with joyful blues phrasing as Krall smiles beside him. His ability to complement a singer was often compared to guitar great Joe Pass, who had famously accompanied Ella Fitzgerald. “Russell is like Joe a great improviser with a deep bag of tricks behind a solo singer. Just when you need something, there it is!” observed guitarist Rod Fleeman, noting Malone’s relaxed, “tasty” backing of vocalists. Malone himself genuinely loved the art of accompaniment. “Listen to how Russell uses chords, moving the harmony around but always keeping the time flowing,” Fleeman added, praising Malone’s sensitivity in a rubato ballad setting.

By the end of the 1990s, after roughly five years with Krall, Malone faced a crossroads. The gig with Krall had made him famous in jazz circles, but he feared being pigeonholed as solely an accompanist. Around 1999–2000, Malone decided to step out of the trio and refocus on his own projects. It was a difficult decision – leaving a successful, high-paying gig but one that would allow him to grow further as a leader. As he later said, he didn’t want to be just “Diana’s guitarist,” even though he cherished that experience.

Going Solo: Leader and Collaborator (2000s)

Malone entered the 2000s determined to carve out a path as a bandleader and all-around jazz guitarist. He released a string of excellent albums under his own name, exploring formats from solo guitar to quartet. His style matured, combining the straight-ahead swing of classic jazz with touches of R&B, gospel, and even pop. For Verve Records he recorded Look Who’s Here (2000) and Heartstrings (2001), the latter featuring orchestral arrangements that highlighted his lyrical playing. Critics noted Malone’s “clear, clean, hearty tone and assured but delicate touch,” and an “unerring sense of swing” tempered by good taste.

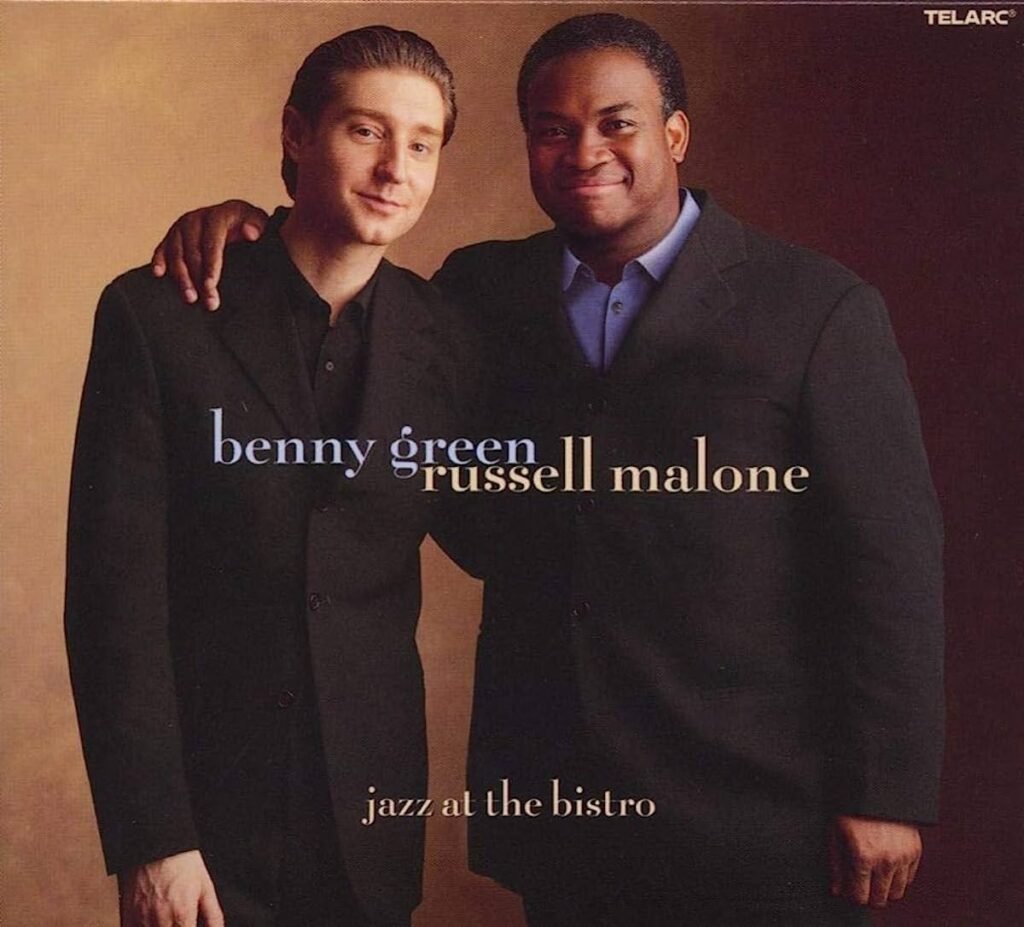

Equally significant were Malone’s collaborations with other top jazz artists. In the early 2000s he and pianist Benny Green recorded as a duo on Live at the Bistro (2003) and Bluebird (2004), touring together through 2007. Their interplay on tunes like “Oscar’s Blues” and “Honeysuckle Rose” paid homage to classic swing traditions while crackling with youthful energy.

Malone also found himself playing alongside jazz royalty. In 2002, legendary bassist Ron Carter invited Malone to join his trio for The Golden Striker. This group, known as the Golden Striker Trio (with Carter on bass and initially pianist Mulgrew Miller, later Donald Vega), became one of Malone’s long running associations. The trio toured internationally on and off for the next two decades, and Malone’s tight bond with Carter deepened over time. In fact, at the time of Malone’s death in 2024, he was on tour in Japan with Carter’s Golden Striker Trio, coming full circle in their collaboration.

During the 2000s Malone recorded steadily as a leader for independent labels. Notable releases include Playground (2004, Maxjazz), which presented his fluid bop lines in an organ trio setting, and live recordings at the Jazz Standard in New York yielding Live at Jazz Standard, Vol. 1 (2006) and Vol. 2 (2007). Those live albums captured the soulful fire of Malone’s quartet stretching out on standards and originals. In 2010, he released Triple Play, an album in a stripped-down guitar trio format that demonstrated his fearsome technique and rhythmic authority on swing and blues grooves.

Malone’s versatility made him highly in-demand as a collaborator. He toured with trumpeter Roy Hargrove and vocalist Dianne Reeves in the 2000s, and did session work with a who’s-who of jazz: pianists Kenny Barron and Hank Jones, saxophonists Branford and Wynton Marsalis, organ great Jack McDuff, and many others. He even crossed into pop and R&B spheres on occasion – contributing guitar to recordings by Gladys Knight and jazz-soul renditions with Macy Gray. Malone could seemingly play anything, with anybody. “He fits into every musical situation with ease my favorite type of player,” wrote guitarist Taylor Roberts, marveling at Malone’s total command of the instrument.

One especially meaningful collaboration was with tenor saxophone titan Sonny Rollins. In 2008–2009, Malone joined Rollins’ band, helping the sax legend celebrate his 80th birthday with concerts in New York. For Malone, playing with Rollins – one of the last living giants of the bebop era was both an honor and a challenge. But he was more than up to the task, contributing driving accompaniment and agile solos. It was yet another testament to Malone’s stature that artists of that caliber trusted him onstage.

By the end of the 2000s, Russell Malone had firmly established himself as one of the premier jazz guitarists of his generation. He had released over half a dozen albums as a leader and appeared on countless projects as a sideman. In 2008, he even did a duet concert with iconic guitarist Bill Frisell, illustrating Malone’s openness to different guitar traditions. Wherever he went, Malone earned respect for his deep swing feeling, lush tone, and encyclopedic knowledge of jazz guitar history.

A Respected Jazz Veteran (2010–2024)

The 2010s saw Russell Malone assume the role of an elder statesman in jazz guitar, though he was only in his 50s. He continued to record strong albums, such as Love Looks Good on You (2015), All About Melody (2016), and Time for the Dancers (2017). These records showed that Malone’s playing only grew more refined with age his bop lines flowed with effortless swing, and his chord-melody work on ballads was nothing short of exquisite.

Malone also remained a frequent collaborator on stage and in studios. He rejoined Ron Carter’s Golden Striker Trio regularly, as that ensemble became a staple at jazz festivals. He was featured on Christian McBride’s album and on saxophonist Vincent Herring’s project underscoring that the younger generation of jazz leaders valued his presence. Perhaps most heartwarming, Malone was a mentor and inspiration to up-and-coming guitarists. Many younger players cited his work as a textbook for tasteful jazz guitar. He taught workshops, and in interviews he would often drop names of his heroes, reinforcing the lineage. “He’s a historian… echoes of giants like Wes and Benson are apparent, yet he’s instantly recognizable in his tone and phrasing,” wrote one observer.

Even after three decades on the scene, Malone never lost his genuine love for performing. He toured tirelessly, playing clubs and concerts around the world. In 2022, he appeared with Ron Carter and Donald Vega in an NPR Tiny Desk (Home) Concert recorded at the Blue Note Jazz Club in NYC. In that intimate video, one can see Malone’s gentle smile as he comps behind Carter’s bass solos, then hear his guitar take the spotlight with fluid single-note lines. The trio’s interplay on tunes like “Candlelight” and “Eddie’s Theme” is a masterclass in subtle, swinging teamwork. It’s remarkable that even in his late 50s, Malone played with the same joie de vivre and commitment to melody that he had as a young man with Jimmy Smith.

Tragically, what no one knew was that these would be some of Malone’s final recordings. In August 2024, Malone traveled to Tokyo for a run at the Blue Note Tokyo with Ron Carter’s trio. By all accounts, the first three nights of the engagement went brilliantly. On the fourth night, the club announced Malone would not appear due to illness. The heartbreaking news soon emerged: after the third night’s performance, Malone had suffered a massive heart attack and passed away on August 23, 2024. He died doing what he loved – performing on stage – with his trusted bandmates by his side. His sudden death at 60 sent waves of grief through the jazz community. Bassist Corcoran Holt wrote in disbelief, “Man, this is so hard to believe… Rest in power Russell. Truly one of a kind. A master musician, a book of knowledge, a book of humor, and a true inspiration.” Pianist Benny Green simply stated, “There goes a piece of my heart.”

Ron Carter, bereaved at losing his longtime guitarist and friend, released a poignant statement accompanied by a photograph of an empty chair on the bandstand. “Donald Vega and I are completing this tour as a duo,” Carter wrote, “In respect and honor of the memory of Mr. Malone… this is the chair Mr. Malone sat in to play and represents his continued presence on the bandstand with us.” That empty chair spoke volumes to anyone who has felt the loss of a bandmate. Malone had meant so much to his fellow musicians – not only for his playing, but for his camaraderie on and off stage.

Musical Style and Influence

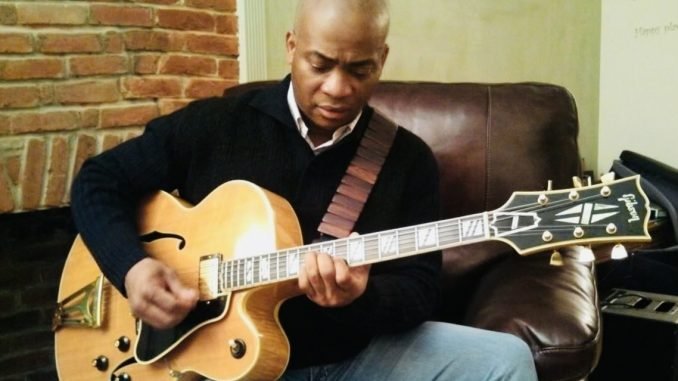

Russell Malone’s guitar style was an elegant synthesis of jazz tradition and down-home soul. He had a clear, warm tone on his archtop guitar often a custom Gibson that listeners could recognize from the first notes. He favored a clean sound with just a touch of reverb, allowing the natural acoustic character of the instrument to shine. In his youth he idolized Wes Montgomery, and one could hear traces of Wes’s octaves and mellow blues feel in Malone’s playing. He also loved George Benson, emulating Benson’s fluid runs and plush tone, and was influenced by Pat Martino’s rhythmic drive. But Malone synthesized these influences into a personal voice. He “epitomized straight-ahead jazz guitar for his generation” – his playing swung hard with bebop vocabulary and fearsome technique, yet it was always delivered with grace and bluesy accessibility.

One hallmark of Malone’s artistry was his chord-melody and solo guitar work. In an age when fewer guitarists focus on unaccompanied playing, Malone stood out as one of the best solo guitar performers. He could take any song – a jazz standard, a gospel hymn, even a pop tune – and make it his own on solo guitar. Fellow guitarist John Pizzarelli was astonished by Malone’s solo renditions: “I heard him play ‘How Deep Is Your Love’ (the Bee Gees song) that just blew me away.” Indeed, Malone’s live performance of “How Deep Is Your Love” at the New York Guitar Festival is often cited by fans for its sensitive, spellbinding beauty. He starts by stating the melody with lush chord voicings, then improvises intricate variations, all while keeping a gentle groove a showcase of the emotional depth to his playing. Swinging or soulful, Malone could do it all. “He has different approaches to touching the instrument,” noted guitarist Anthony Wilson. “In an ensemble his playing is more pointed and percussive, but when he plays solo he has a very beautiful softness… I think he is one of the best solo guitar players today.”

Malone was also revered as an accompanist and rhythm guitarist. He had an uncanny sense of time and groove. When comping behind a soloist or singer, he was ever tasteful “always relaxed, never rigid… I can tell he’s hearing the other instruments in his mind as he accompanies solo,” guitarist Rod Fleeman observed of Malone’s duet work with vocalists. Mark Whitfield lauded Malone’s rhythm playing as well, calling him “a guitar player’s guitar player” with total knowledge of the instrument’s possibilities. Whether chunking out Freddie Green-style quarter-note pulses behind a big band or providing sparse color behind a ballad, Malone placed every chord with intention. This made him a favorite sideman for singers like Freddy Cole and Dianne Reeves, both of whom he toured with. “Russell, like Joe Pass, is like a great piano player in supporting a singer,” was how Rod Fleeman summed it up. He made the guitar breathe like a whole rhythm section.

In terms of repertoire, Malone had immense range. He loved the Great American Songbook standards and blues that are core to jazz, but he also ventured into Brazilian bossa nova, gospel tunes, and even occasional classical guitar pieces. Early on, he recorded “Flowers for Emmett Till,” a piece with a classical guitar flavor – showing that even at the start, he could surprise listeners with genre-crossing experiments. Later in his career he might throw The Beatles’ “Something” or a hymn like “Someday We’ll All Be Free” into a live set, imbuing them with a jazz spirit. This open-minded approach made him stand out among straight-ahead jazz guitarists.

Yet for all his virtuosity, Russell Malone’s priority was always melody and feeling. He once said, “How you are as a human being has an effect on how the music comes out,” emphasizing the importance of playing from the heart. He wasn’t interested in flash for flash’s sake. Bassist Christian McBride described Malone’s playing as having “soulful integrity” every note meant something. This integrity won Malone accolades including a shared Grammy Award in 1998 (as part of Roy Hargrove’s Habana) and multiple appearances in DownBeat magazine’s critics and readers polls over the years. More importantly, it won him the love of listeners and colleagues.

Personal Life and Legacy

Off the stage, Russell Malone was known as a humble, kind-hearted man with a playful sense of humor. Those who toured with him often mention his quick wit and easygoing nature. “Swinging, it is so swinging. Russell is a very funny guy. He is the same on the guitar when he starts to play it is always surprising,” guitarist Anthony Wilson said, affectionately linking Malone’s personality with his playful improvisations. Despite performing with so many luminaries, Malone never projected ego. He kept his Southern gentleman charm. In a 2023 interview, Malone said, “I just want to be a good person, be a good human being. I figure if I do that, then everything else will take care of itself.” That genuine modesty and warmth came through in his music.

Malone’s personal life was relatively private, but it’s known that he maintained close ties to his hometown of Albany, GA throughout his life. He would return home to visit often, sometimes even appearing on local TV programs or at community events. He is survived by his long-time partner, Mariko Hotta, and two children, Darius and Marla Malone, along with extended family. One can only imagine their pride in Russell’s accomplishments and the outpouring of love after his passing.

The legacy Russell Malone leaves is multifaceted. Musically, he stands among the great jazz guitarists – a link in the chain that connects Wes Montgomery to the future. He carried the torch for mainstream jazz guitar in an era when trends often veered elsewhere, and he did so with authenticity and soul. Numerous young guitarists cite him as an influence, studying his recordings to learn the art of tasteful phrasing. His recordings as a leader (over 13 albums spanning 1992 to 2017) will continue to be listened to by jazz aficionados, and his sideman work – from Diana Krall’s beloved albums to Ron Carter’s trios – ensures his sound will reach new listeners for years to come.

Just weeks into 2025, the jazz community paid tribute to Malone in an emotional musical celebration at Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York. On January 8, 2025, an all-star lineup gathered in the Appel Room to honor the late guitarist. Ron Carter, Kenny Barron, Monty Alexander, Christian McBride, Benny Green, Diana Krall, and many others who had known or been touched by Malone’s music performed in his memory. The stage was filled with guitars – peers like Ed Cherry, Dave Stryker, and Russell’s protégé Yotam Silberstein all playing their hearts out and singers like Tammy McCann offering musical eulogies. It was a night of “joyful remembrance,” celebrating the swing, blues and groove that Malone brought to every note he played. As one report described, the concert felt like a family gathering, simultaneously mournful and uplifting, much like a New Orleans jazz funeral where tears and laughter mix.

In the end, Russell Malone will be remembered not only for how he played, but how he made others feel. His music had a warmth that could bring tears to your eyes or make you smile with a sudden witty riff. He connected with audiences on a gut level, whether in a small club or a concert hall. Fellow guitarist Bobby Broom said he could always identify Malone on a recording by “his rhythmic approach” a certain joyful bounce and clarity that was uniquely Russell. And as Corcoran Holt wrote, Malone was “truly one of a kind… a true inspiration” to those who knew him.

The jazz world lost a giant far too soon, but Russell Malone’s spirit lives on in his music and in the countless lives he touched. From the little boy in Georgia strumming a toy guitar, to the seasoned artist still pushing himself onstage in Tokyo – it was a beautiful journey. Thank you, Russell, for the melodies, the swing, and the humanity you shared through six strings. Your music will keep ringing out, ensuring that your memory in jazz history remains ever green.

This post was created by Peter Antheunis

I created this post using these sources: obituaries and tributes (including those in the New York Times, The Washington Post, and JazzTimes), biographical and discographical data from AllMusic and Discogs (supplemented by liner notes from albums such as Russell Malone (1992), Black Butterfly (1993), When I Look in Your Eyes (1999), Look Who’s Here (2000), Heartstrings (2001), Playground (2004), Triple Play (2010) and Love Looks Good on You (2015)), interviews and personal statements published in JazzTimes, DownBeat, GuitarPlayer, Jazz Guitar Today and NPR (including comments by Malone himself, Anthony Wilson, John Pizzarelli, Rod Fleeman, Henry Johnson, Christian McBride, Corcoran Holt, Benny Green and Ron Carter), performance footage and audio sources (notably the 1996 Montreal Jazz Festival “Route 66” video, the 2022 NPR Tiny Desk Concert with Ron Carter and Donald Vega, the New York Guitar Festival solo of “How Deep Is Your Love” and Blue Note Tokyo engagement materials), and festival and tribute event materials (including the January 8, 2025 “Celebration of Russell Malone” at Jazz at Lincoln Center, Montreal Jazz Festival archives and Blue Note Tokyo press releases).

Responses