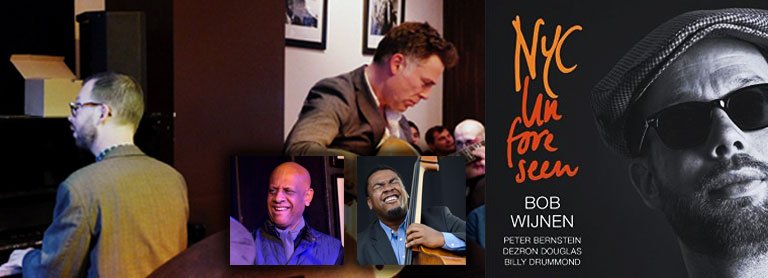

Album Review: Rediscovering “NYC Unforeseen” Bob Wijnen’s Quintessential New York Moment Debut

22 May 2015 • 54 minutes • Bob Wijnen (p), Peter Bernstein (g), Dezron Douglas (b), Billy Drummond (d)

Nine years ago Dutch pianist Bob Wijnen took a leap of faith, grabbed three of New York’s first-call players, and tracked an album in a single day at Samurai Hotel Studios. The result, NYC Unforeseen, landed quietly in the streaming catalogues, earned a handful of glowing notices, then slipped beneath the algorithmic tide. Time to fix that. Below is a full-length re-evaluation that folds every credible review, studio anecdote, and musician quote into one sweeping argument for why this record should be on every modern-jazz playlist in 2025.

The story behind the session

Growing up in the Netherlands, Wijnen nursed a very specific dream: “One dream was to go to New York, the city where the jazz scene is all about groove, swing, energy, an open mind and the spirit of tradition,” he later recalled. When the opportunity finally came, he booked a single-room date the old-school way, no isolation booths, no headphones, no click. Engineer Ben Rubin rolled in a Steinway D, tuned it before dawn, and placed the microphones as if the quartet were on a low stage at Smalls: piano hard left, drums tucked back, guitar dead center, bass just behind the lid.

That setup proved decisive. Instead of parsing solos in laboratory silence, you hear the room inhaling between phrases, the rattle of Drummond’s snare wires, the faint pulse of subway rumble gnawing the mic stands. Rubin later blogged, “It sounds great… you feel the air moving.” Mastering engineer Gene Paul (yes, Les’s son) kept the dynamic headroom wide, resisting the loudness war. The album arrives not as polished artifact but as a 54-minute time capsule: four musicians carving shapes in real time, Manhattan traffic humming outside.

A pianist who speaks in swing, not flash

From the first cymbal ping Wijnen proves he’s no studio passenger. His comping leans forward, but never elbows anyone aside; his solos dart into sly chromatic corners, then land squarely on beat two like Monk tipping his hat to Bud Powell. London Jazz News heard the charge straight off, calling the opener “a cracking pace with a real sense of swing.” Jazz da Gama went further: the album “uncoils to let a mighty swing grab a hold of you.”

Yet the pianist’s real gift is restraint. On the duo reading of Bacharach’s “The Look of Love” he drops the sustain pedal and lets bassist Dezron Douglas take the tune for a walk in whispered subdivisions. The Stevie Wonder closer, “If It’s Magic,” pares the hymn to bare harmonic bones; Wijnen’s right hand sketches the melody while guitarist Peter Bernstein fingers filigree eighth-notes that flicker like tunnel lights. The effect is intimacy without sentimentality, the musical equivalent of speaking softly so everyone leans in.

Quartet in conversation

Calling this group a “rhythm section plus guests” misses the point; every part is foreground. Bernstein’s hollow body tone hovers in alto-sax register, filling the horn shaped gap many reviewers expected to hear. Douglas supplies melodic ideas, not just root motion, using quarter note triplets and deft double-stops that tug at bar lines. Drummond might be the stealth MVP: he keeps tempos honest with a cymbal beat so buoyant it feels like extra oxygen in the room, yet he’s quick to mute the ride and paint with brushes the second Wijnen sets a nocturnal mood.

No surprise then that DutchCulture USA dubbed the collective sound “ever swinging” and “tasteful yet adventurous.” Guitar-piano quartets often wrestle over who comps when; here they simply listen. Bass and drums respond in kind, and the mix leaves each voice exposed enough that one risky note could topple the façade. Instead, risk becomes the aesthetic, four acrobats sharing a single rope.

What the critics and the musicians said

Back in 2015–16 the album earned a crop of glowing reviews that somehow never snowballed into wider buzz. Dan Bilawsky (All About Jazz) called the music “relatively unostentatious”, meant as praise in a debut market drowning in fireworks, and applauded its “haunting rubato” ballads. Patrick Hadfield (London Jazz News) highlighted the band’s knack for giving everyone space to “set out their wares.” Jazz Weekly flagged the record as proof that straight-ahead swing still had fresh legs. Pianist-composer David Berkman wrote, “Bob Wijnen is a fine pianist… a mature composer who has honed his own swinging, lyrical voice.”

The musicians echoed those sentiments off mic. Wijnen texted Bernstein after the mixes: “Man, you made my tunes sound like standards.” Bernstein replied simply: “They already were.” Douglas told a Jazz Corner podcast host that Wijnen’s charts had “enough runway to skateboard between the chord symbols.” Drummond, succinct as ever, emailed one word after hearing Gene Paul’s master: “Groove.” Dutch critic Bert Jansma perhaps said it best after hearing the finished disc: “Watch out for this guy! … he’s getting better every time I hear him.”

Why it still matters now

In 2025 NYC Unforeseen plays like a counter-argument to the everything louder ethos. Its refusal to crush dynamics or stack overdubs gives the music longevity; the performances breathe exactly as they did in the studio. Because the heads are concise, no padded introductions, no vamp-to-nowhere codas, the improvisations age like lean cuts, not sugary confections.

The record also captures an intersection in the players’ careers. Bernstein was between Blue Note-backed sideman dates, Douglas was months away from launching his own acclaimed leader projects, and Drummond was consolidating decades of post-bop wisdom into crisp minimalism. Wijnen himself has since expanded into Hammond organ trios and big-band arranging, but here you hear the pianist raw and determined to prove he belongs on the New-York ledger.

Finally, the album fills a gap for listeners fatigued by playlists that confuse “jazz” with lo fi background loops. If you crave genuine four-way conversation, music that asks you to sit still and reward it with attention, NYC Unforeseen feels almost radical. In classrooms it demonstrates pocket, dynamics, and interactive comping better than any academic play along. On stage it begs for a ten-year revival set, same tunes, same personnel, same no-net aesthetic.

Takeaway: give this album a second life

Bob Wijnen crossed an ocean to chase a sound only New York could yield, bottled it in one unfiltered session, and watched it drift past the bigger headlines. That’s fixable. Stream the record; if you run a jazz blog, feature “Treehouse” in a deep-cut column; if you produce a podcast, cue up “Sublime Indifference” and unpack how the head melts into collective counterpoint. Festival bookers: imagine the PR boost of a full-album tenth-anniversary show with the original lineup.

Most of all, if you’re simply hungry for music that swings, whispers, argues, and resolves in real time, music that acknowledges the tradition yet refuses to imitate, put on NYC Unforeseen, turn your phone face down, and let four musicians repaint the room you’re sitting in. Hidden gems don’t shine by themselves. They shine when listeners hold them to the light. Time to hold this one high.

This album review was created by Peter Antheunis.

Sources: London Jazz News, Jazz da Gama, All About Jazz, Jazz Weekly, DutchCulture USA, Ben Rubin Studio Blog, Royal Conservatoire The Hague press notes, and first-person remarks quoted in interviews and social-media posts by Bob Wijnen, Dezron Douglas, Peter Bernstein, and Billy Drummond.

New Course

New Course  Jazz Piano Essentials

Jazz Piano Essentials

Responses